4 Lessons From Shoulder Surgery 10 Years Ago

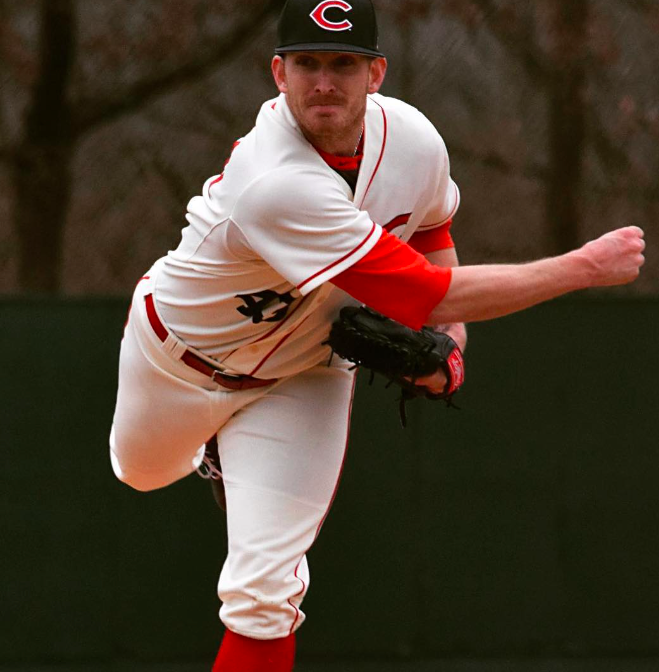

A decade ago, just after my junior season of my college baseball career ended, I had shoulder surgery to repair a torn labrum. In some ways it feels like it was just yesterday; but really it feels like an entire lifetime ago. I think (and hope) I’ve learned and grown a lot since then.

In retrospect, it was the single-most impactful event on the course of my life.

It drastically altered the path I was on. It forced me to deal with adversity, pain, and regret, all of which made me a stronger, more compassionate, and ultimately and in a strange twist of fate – a much happier person.

It led me into coaching baseball and got me into strength and conditioning. Before it happened I had absolutely no thoughts or desire to go into either of those fields.

It allowed me to coach my younger brother of seven years which helped forge a deep bond and one of the most important relationships in my life. It allowed me to coach dozens of other players who are like younger brothers to me to this day as well.

Here are some lessons I learned from that surgery:

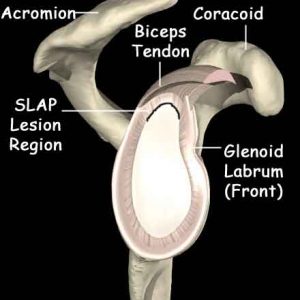

- Healthy Shoulders Can Have Seriously Abnormal MRI Findings

You can have a torn labrum and be pain free. In fact, Miniaci et. al found that nearly 80% of asymptomatic professional pitchers had ‘abnormal labrum features’. Furthermore, they stated that, ‘MRI of the shoulder in asymptomatic throwing athletes reveals abnormalities that may encompass a spectrum of nonclinical findings.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11798999/

This isn’t limited to just baseball players but other overhead athlete populations as well. In another study, Connor et al found that 40 % of asymptomatic baseball players and tennis players had partial or full thickness cuff tears under MRI.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12975193

Think about this. 40 percent (8 of 20) ASYMPTOMATIC (pain-free) dominant shoulders showed a partial or full labral tear.

You may be thinking, how can people with fully torn labrums be without pain while still playing baseball or tennis at a high level? This leads me to my next lesson.

2. A Movement Diagnosis Is As Important As a Medical Diagnosis

A medical diagnosis is certainly important, however, of equal (and perhaps greater) importance is a correct identification of the underlying issues that led to the injury reaching threshold.

These issues (such as abnormal labrum findings) often only become symptomatic when someone doesn’t move well, has poor soft tissue quality, lacks strength, or has poor mobility. Oftentimes it’s a combination of all the aforementioned.

In my case, my MRI report back in 2011 showed a partially torn labrum, and tendinosis of the supraspinatus, teres minor, and infraspinatus. My pain was most certainly caused by having tendinopathy in three of the four rotator cuff muscles, and not by the torn labrum.

I didn’t know back then what I know now – and unfortunately was really let down by multiple people that were in charge of my rehab. The above was my medical diagnosis, but there was no real movement diagnosis. I was given a cookie cutter rehab program and six months post-op when I went to start my return to throw program, I hadn’t improved upon any of the underlying conditions that led to me getting hurt in the first place.

I ended up re-injuring my shoulder multiple times and never even got to the mound phase of the return to throw.

It wasn’t until years later, when I had built up a ton of strength and improved my posture, upper extremity function and soft tissue quality where I was finally able to throw hard and without pain again.

3. You Have To Earn The Right To Throw Again

Throwing a baseball is the single-most stressful movement in all of sport. The head of the humerus internally rotates between 7000-9000 degrees per second on a pitch 90 mph or greater. And that’s just once. Multiply that by a hundred in a game and extrapolate it over years and years and you can understand why arm injuries are unfortunately commonplace among the throwing population.

With the pitchers who rehab with me, throwing is the last hurdle. I may not have my pitchers bench press, do pull ups, and press while they are throwing, but we had better feel confident and strong doing those activities before being cleared to throw. They are not nearly as stressful as throwing itself.

I often say that more work and patience on the front end of rehab will pay off down the road.

4. The Traditional Return to Throw Leaves A Lot to Be Desired

I have overseen several high level throwers’ rehab programs , and we’ve had some really good success by deviating from the traditional return to throw program, once we pass the 120 foot stage.

After the athlete has completed 3 sets of 25 throws at 120 feet, we then move on to what I call Phase B, or a long toss phase. The goal here is to eventually progress them over a few weeks to max. distance long toss. In the traditional return to throw, the athlete gets on the mound once they’ve thrown 180 feet.

To me this just doesn’t make sense. Throwing off the mound is more stressful than throwing off flat ground(due to the increased valgus stress of being on a slope). We want to build up our long toss intensity, and essentially we skip throwing off the mound at 50 %. I don’t see a lot of merit in throwing lightly off the mound. I would prefer to build up the athlete’s tolerance to both volume and intensity through long toss.

The traditional return to throw protocol follows a linear periodization model, and ultimately the athlete begins to lose their general long toss preparation in exchange for throwing off the mound more frequently.

Once the thrower can get after long toss at max or near max effort, we then progress to Phase C: throwing off the mound. At this point they work at an 8/10 RPE. Over 4-6 weeks they build up to throwing 40-50 pitches at that effort level. Next is throwing at max effort off the mound.

If you’re a thrower going through an injury or have any questions, please feel to reach out to me – I’d love to help.